the 5 main causes of back pain.

I, like most doctors, was taught two myths about back pain:

You can’t diagnose lower back pain

back pain goes away quickly

These myths have lead to back pain being ignored as an important problem as the prevailing attitude has been “You can’t diagnose it, and it will go away anyway, so don’t worry, you’ll be OK”. My kids would refer to this as an “internet fact” not a “true fact”. Eighty percent of people will suffer lower back pain at some time in their life. Although, the minority (20%) recover fully, most (80%) of people still complain of pain at 12 months. 5% suffer low grade pain, 15% moderate levels and 10% are significantly disabled (Von Korff M, Saunders K. Spine 1996). Said differently, at some time in your life you are likely to suffer back pain that lasts for 12 months, or longer. The diagnosis of the cause of lower back pain is also now possible in most cases. “Non-specific lower back pain” is no longer “Non-specific”.

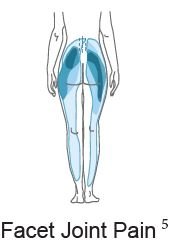

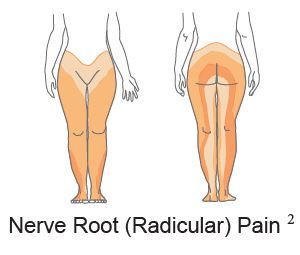

There are 5 main causes of lower back pain; facet joints, sacroiliac joints, hips, discs, and nerves. To help identify which one is the primary cause of pain, we utilise a range of standard questions like what triggered it, where it’s located, where is radiates, what makes it better or worse and any associated symptoms to try pin down which one is the culprit. Unfortunately, many of the answers are not specific for one structure and if the patient is in a lot of pain, everything hurts. Above is a picture of the referral patterns of sources of lower back pain - sacroiliac joint (yellow), facet joint (blue), hip (purple), disc (green) and nerve root pain (orange). As you can see they all overlap, making it difficult to identify pain simply based on where it’s felt.

In this situation, you would think a scan may be of use. Unfortunately, this is commonly not the case. For lower backs, 83% of people with NO PAIN will have a disc degeneration, a bulge, protrusion or extrusion. With a range of other changes just being “wrinkles” on a scan. The picture on the left gives you an idea of what is “normal” on a back MRI.

You can’t just match up the scan results to where the pain radiates from. The way to diagnose lower back pain is to block or “numb up” specific structures or their nerve supply, and see if the pain goes away. This is done in a step by step fashion starting with the most likely structure based on history, examination and imaging findings. Numbing up the area is commonly done twice with different local anaesthetics to confirm the pain actually goes away. If done is this way, 85% of the origin of pain can be identified.

The Big 5

Facet Joint pain

Facet Joint Pain

The first of the “Big 5” is facet joint pain. The facet joints sit at the back part of the spinal column and are the source of back pain in at least 30% of people. When people speak about having arthritis in their back, this is probably the part that is affected. However, arthritis in backs is common and in most cases doesn’t actually hurt. As you get older is it more likely back pain is coming from facet joints, however, on MRI’s of people with NO PAIN at age 80, 83% of people have facet joint arthritis. So just because it is on the scan, doesn’t mean it hurts.

The symptoms of facet joint pain are non-specific and overlap with other structures from the back. As a rule of thumb, the pain is an ache above the belt line, tennis ball or larger in size, and commonly more to one side or the other. It can radiate down the leg as far as the calf and very regularly gets labelled as “Sciatica”, but is it not. The pain is generally worse with bending backwards, and in the morning is associated with stiffness that improves as you warm up over 10-30 minutes. If you are being examined by a doctor they may try to reproduce your pain by pushing over the facets and doing a test called the Quadrant Test. This is done by bending backwards and to toward the side of pain, trying to reproduce the “usual” pain. Interestingly, if you have no pain when doing this it makes it unlikely the pain is coming from your facets.

Confirming that facets are the source of the pain is done either with facet joint injection or by blocking the nerves that supply the facets. This is known as a medial branch block. Although, you would think injecting the facet directly would be a good test, it turns out it isn’t because of leakage out of the joint. As a result we tend to avoid these and perform medial branch blocks. Medial Branch blocks use a very small amount of local anaesthetic to numb the nerves that supply the joints. It is performed on 2 separate occasions and if the pain goes away both occasions, it is highly likely the facets are responsible for the pain.

To be able to “fix” the joint would be great, but at the moment, there is no such solution. Treatment is aimed at decreasing the pain arising from the joints rather than “fixing” them. This is done utilising multiple techniques including medications, rehab and exercise. In addition, the pain signal can be disrupted from getting from the facet joint to your brain by a process known as radiofrequency ablation. This process heats the same nerves we blocked during medial branch blocks. Radiofrequency ablation is effective in 60-90% of people, and results in 60-90% decrease in pain for 9 -18 months. In many people, when the nerve regenerates the pain does not return, however if it does, it can be repeated with expectation of getting a similar period of pain relief. With regards to stem cells, there has been some anecdotal reports in the media about their success, but nothing published to my knowledge in the scientific literature. It is certainly an area that may be effective and we will likely be looking at a study using cells in people with confirmed facet joint pain that have failed normal treatment, in the future.

Sacroiliac Joint Paint

Sacroiliac Joint Pain

Sacroiliac joints are just below the facet joints. They are the joint that connects your back to your legs and move very little. About 15-30% of back pain is said to arise from sacroiliac joints but it gets more common as patients get older (Schwarzer et al, 1995, Dreyfuss et al, 2004, Rathmell 2008, Depalmer et al, 2011).

The pain of sacroiliac joints is similar to that of other structures in the back. The pain is a deep ache through to sharp pain. It rarely goes above the belt line (Dreyfuss, et al, 2004b) and refers to both buttocks (94%), thigh (50%), calf (28%) and foot (14%) (Slipman et al, 2000). A golf ball sized area of pain over the SIJ and just below the posterior superior iliac spine (“bony bit” at the back) that contains the majority of their pain, indicates the SIJ may be the source of pain (Dreyfuss, et al, 2004b). Asking the patient to point to the majority of the pain with one finger can also be very helpful.

The pain is generally worse with sitting, moving from sitting to standing, lying flat and rolling over in bed and going down stairs. There are a range of tests used to examine the sacroiliac joint, no one of them is truly effective at confirming the diagnosis and they need to be used together to add to the whole picture. Scans are not useful, unless an inflammatory arthritis, such as ankylosing spondylitis is suspected.

Diagnosis is once again done by numbing up the joint. This can be done in a similar fashion to facets by either injecting the joint or blocking the nerves that supply the joint. There is argument on which is more effective, however, both may be used on separate occasions to confirm if the SIJ is the source of pain.

In addition to the SIJ being painful it may also be loose. This is a controversial area and many clinicians will disagree that the SIJ can move or be loose. I likely have a biased population of patients that do appear to have SIJ laxity or pelvic instability, who improve when it is treated, so I am in the group of clinicians that think the condition exists.

Pelvic instability occurs as a result of the pelvis being excessively mobile, or “hypermobile”. The classical presentation is post-pregnancy. Pelvic hypermobility arises due to loosening of the ligaments during pregnancy in preparation for birth of the child. Once the baby is born, hormone levels drop and ligaments should stiffen back up. However, in some women this doesn’t happen, and they might develop significant SIJ or pubic symphysis pain. This is commonly accompanied by a sense of weakness and muscle tightness about the pelvis. The weakness occurs because as the muscles attempt to contract, the pelvis shifts, thus they don’t contract effectively and feel “weak”. The tightness arises as the muscles attempt to compensate for the loose ligaments, and tighten to stabilise the pelvis. In the setting of having babies the ligament laxity and pelvic instability makes sense, and it is quite well accepted and treated. For those who haven’t given birth, pelvic instability due to ligament laxity is harder to grasp. I see ligament laxity as being on a continuum from “stiff” to “hypermobile”. Those who are on the “stiff” end of the continuum tend not to have issues with pelvic instability, unless they have suffered a fall. The classic is “I fell down some stairs and landed on my bum”. This can result in a fracture of the pelvis or the SIJ being subluxed and becoming unstable. At the other end of the continuum are those that are hypermobile. These people generally do well in sports such as dancing or gymnastics that require a large degree of flexibility. The down side is they tend to have ligaments that are closer to those of pregnant women, therefore more frequently suffer pain related to pelvic instability.

Some anecdotal hints that pelvic instability may be playing a role. The pain is below the belt line over the buttock, with associated pain over the outside parts of the hips (commonly incorrectly labelled as bursitis), and pain over pubic symphysis. There tends to be a sense of muscle tightness across the buttocks and groins. The pain is better when crossing your legs and worse when rolling over in bed. As part of treating pelvic instability, many people try to do pilates to help strengthen their “core”, however, due to the loose ligaments, most people fail to progress and frequently find their pain get worse or flare after exercising.

Treatment of SIJ pain is dependent on the cause. If you solely have SIJ pain that resolves with blocking the joint or the nerves that supply it, radiofrequency ablation can, once again, be effective. There are unfortunately no randomised control trials of SIJ radiofrequency ablation. However, there has been a large case series of 300 patients published. (Mitchell et al, 2015). This showed that 70% of people get 70-80% pain relief that lasts on average 9-18 months. For the 30% that don’t get relief, it’s probably because the diagnosis is wrong (12%) or they have nerve supply from the back and front (20%) of the joint. Unfortunately, we can’t get to nerves at the front. For the first 2 weeks after the procedure there can be some worsening of the pain, but this only last to 6 weeks in 1% of people and 6 months in 1 in 1000. This can be well managed with topical creams for the duration of pain.

If the pain is arising from the SIJ in the setting of SIJ laxity or instability, treating the instability can be an effective way of addressing the pain, but this is controversial. Simple measures include using sacroiliac joint belts and exercise that improves muscle strength about the pelvis. If this is unsuccessful, prolotherapy can be effective. Prolotherapy is the injection of concentrated glucose solution into the ligaments. This results in an inflammatory reaction and stiffening of the ligaments. It has been shown to improve function in 78% of patients (Cusi et al, BJSM 2010 and completely decrease pain in 40% of patients, significantly decrease pain in 30%, 20% have improvement by require further intervention, and 10% gain no benefit (Mitchell, et al, JSAMS 2015).

Discogenic and Nerve Pain

This instalment of the “Big 5 of lower back pain” covers disc and nerve pain. I have grouped them together as they are commonly confused as being the same thing, but put simply they’re not. That said, they regularly occur together, thus the confusion.

So what is the difference? From my point of view the main difference is that “Nerve pain” is really easy to diagnose, the treatment options are clear cut and I can get on with it. Disc pain, on the other hand, is hard to diagnose and much harder to treat and generates all number of frustrations for the both the person suffering and the person treating.

Nerve Pain

Pain generated due to compression of a nerve root presents in 2 different ways. The 1st type of pain is an electric shock that runs from your bum and fires down the back of your leg and comes out your toes, this is known as Radicular pain. If the pain shoots out your big to it is probably L5 that is being effected, if its’ your little toe (or outside of your foot) it is likely S1. If it doesn’t make it down to your foot and stops at you shin it will probably be L4 and if stops at the inside of your knee, then L3. The second type of pain is in the same general pattern as Radicular pain but is achy rather than like an electric shock and it can be combined with burning, pins and needles, numbness or weakness of particular muscles (this is technically called a radiculopathy).

Enter the confusion. Both these types of pain are referred to as “Sciatica”. The confusion doesn’t come from radicular pain, as this is a very specific type of pain and easily diagnosed. The problem is the achy pain. All the big 5 of lower back pain can give you achy pain down your legs. This type of pain is referred to as Somatic referred pain. ‘Soma’ means body, I think of it as “pain from a body part”. The question is “Which part?” Is it facet, sacroiliac, hip, disc or nerves? Once it is labelled as sciatica, the doctor is diagnosing the pain as being caused by nerve root compression, but as multiple things cause this type of pain, this is not necessarily the case. The confusion worsens as MRI’s get added to the mix. Twenty two percent of people with no pain have nerve root compression on their scans. So just because something is on the scan, doesn’t mean it is the source of pain. A hint that somatic pain down the legs is coming from a nerve root is that the pain tends to be worse in the legs than the back, tends to be in a more specific pattern (in doctor language we refer to it as “dermatomal”) and can be associated burning, pins and needles, numbness, weakness or decreased reflexes.

Disc Pain Coming Soon…

Hip Joint Pain

Hip Pain

Hip Joint Pain Coming Soon…